A high school graduation in Palestine: it never entered my mind to seek out such an opportunity, but here we are with our friend, Yasser, one of the teachers at the Rosary Sisters’ High School, a private Catholic girls’ school in Beit Hanina. It is near 5:00 PM on a Thursday evening—we’re not late, but we arrive later than scores of students and their families, so parking is a problem. Cars are tightly parked in every available space and are angled this way and that. Yasser is unable to park in the faculty lot because it is already filled…so he drops us off and goes searching for a space. When we enter the auditorium, it is already filled with people holding balloons and flowers and cameras. All ages of people are dressed up for this celebratory occasion—suits and ties, colorful dresses and hijabs.*

We are seated in the front of the room, just behind Yasser, in a place reserved for “special guests.” I am the only blond-haired person in the room—casually dressed, too (we thought we were going to a party—a problem in translation), so I feel a bit obvious. We are in an auditorium with a balcony at the back of the room and a stage in the front of the room. The school’s logo is projected onto a screen, high up on a curtain at the back of the stage, in a “now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t” kind of rotation. A set of bleachers frames each side of the stage at 45-degree angles. There is laughter and excited chatter of voices speaking a language I can’t understand, so I experience the voices as percolating sounds bubbling around me. It is interesting to be immersed in a room filled with voices and not understand what is being said—to just listen without word-meaning distraction.

As the young women enter the room in a procession with their teachers, there is excitement and joy: clapping, cheers, smiles and the flashing of cameras. The young women are dressed in their school uniform—a red and blue plaid jumper with a long-sleeved cotton white blouse—and, with the exception of two (one with dark blond hair, the other with red hair), they have long, dark and carefully styled hair. Ninety-four young women file onto the bleachers, and their faces are beaming.

During the next two hours, we hear selected students presenting their parting thoughts in three languages: English, French and Arabic. We observe underclasswomen dancing—their bodies held straight and strong: classical ballet, contemporary modern, and the dubka, a traditional Arab folk dance. We hear singing of the national anthem of Palestine and see pride in the countenance of these young women. And, finally, we watch each student being acknowledged as she receives her diploma from the principal of the school, Sister_____.

The room is significantly warmer than it was earlier and on the stage where the young women who have received their diplomas are standing, even warmer. About mid-way through the awarding of diplomas there is the sound of something dropping on the stage, followed by alarmed voices, a break in the composure of students standing there, and a rush of movement towards the back of the stage. A student has dropped to the floor. Then, from another section of the stage, another student drops to the floor. A doctor in the audience rushes to the students, as do several parents concerned for their daughters. After he checks them out and they are helped off the stage, we learn that they have fainted–probably an effect of the heat and insufficient intake of water–and are otherwise OK. As the room’s anxious energy calms, the ceremony continues.

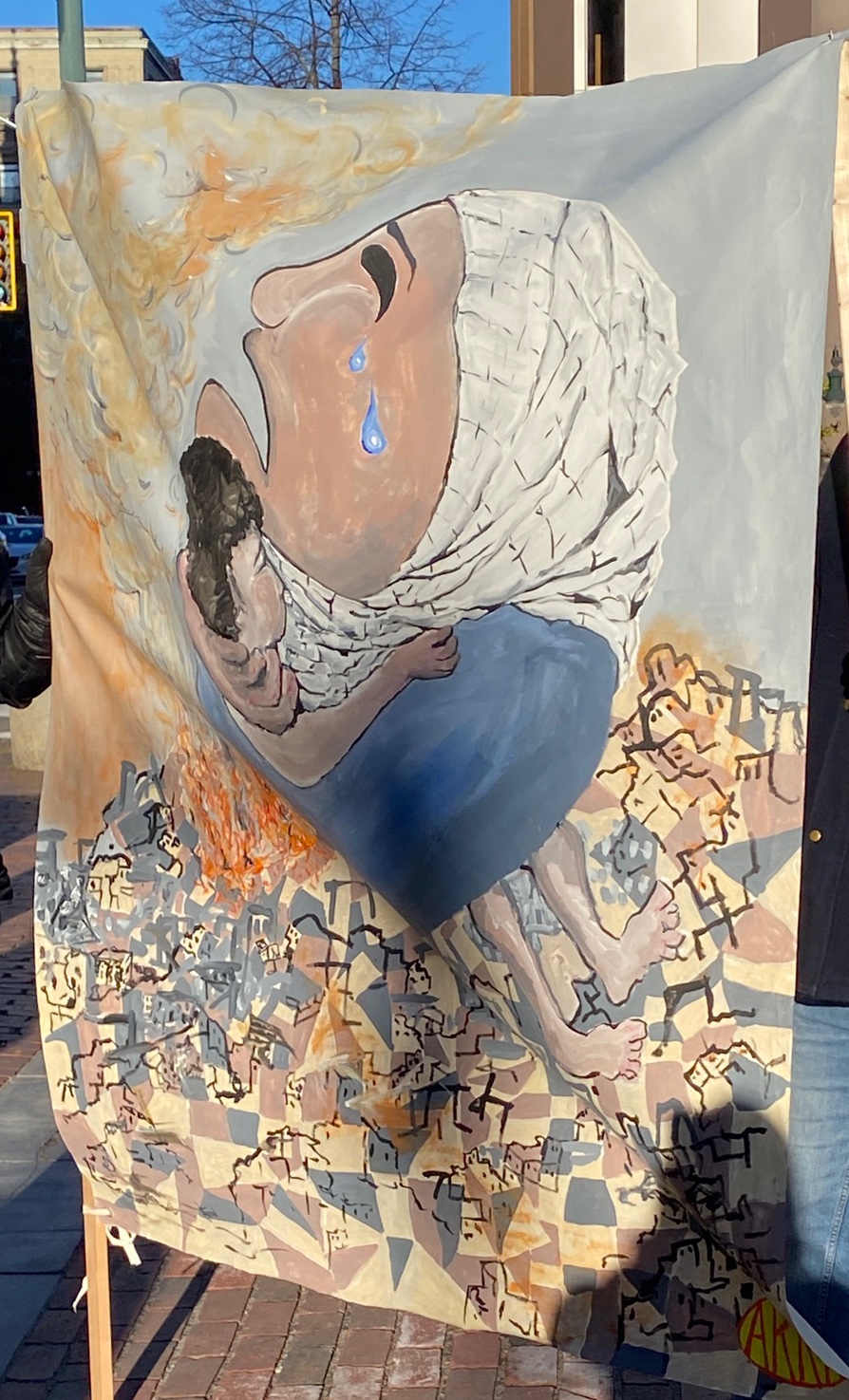

Later that evening, as we return home to our apartment, Yasser tells us that before the graduation ceremony there had been a protest outside the school. This year, like the many years before, the principal has not allowed Muslim girls who wear the hajib to do so at graduation. They either comply with this restriction or not participate in the ceremony. So, sixteen girls this year did not participate. (The nuns, including the principal, however, have always worn their head coverings, as they did this evening. I find this curious.)

Teachers, teachings and a supportive community—The Buddha understood the importance of these three elements (referred to as the “Three Jewels”) in following a spiritual path. Aren’t these elements, too, important on the entirety of the journey that is our life? Couldn’t living life be described as a spiritual journey—a seeking of meaning and purpose and happiness? All are present here this evening.

These young women manifest the fruits of the teachings provided by their teachers and the love and support they have received from their community. Seeds not yet sprouted have been planted, too. Just as soil is prepared to nourish and sustain the growth of flowers and plants and trees, so the minds and hearts of these young women have been prepared to grow in wisdom, strength and compassion. Life’s roughness and richness and sorrows and joys will be the nutrients; and the “three jewels,” the soil and the seeds.

In occupied Palestine, the roots of life and connection to the land are strong. With continued nourishment and proper conditions, these young women will grow and flourish— May their lives be of benefit to the people of Palestine and to all beings near and far.

*Headscarves covering the hair of Muslim woman. (Contrary to what many people believe, not all Palestinians are Muslim and not all Muslim women choose to wear the hijab. Also, the hijab is not the same as a burka, which is a full face and body covering.)